Section 3.1 Recursion and Iteration¶

This week’s section exercises explore the ins and outs of content from week 3 – thinking recursively! These problems will help in gaining familiarity with recursive problem-solving.

Recursion and Iteration¶

Eating a Chocolate Bar, Take Two¶

Last week, you explored what it was like to eat a chocolate bar where, at each point in time, you could either eat one square or two. But who are we to tell you how many squares you can eat at once? You’re an adult, and you can make your own decisions! If you want to eat five squares at a time, or cram the whole chocolate bar in your mouth in a single bite, go for it!

This increases the number of ways of eating the chocolate bar. For example, here are all the ways to eat a \(1 \times 4\) chocolate bar:

1, 1, 1, 1

1, 1, 2

1, 2, 1

1, 3

2, 1, 1

2, 2

3, 1

4

As before, order matters. Last time, we wrote the following function, which counts the number of ways to eat a chocolate bar using bites of sizes 1 and 2.

int numWaysToEat(int numSquares) {

/* Can't have a negative number of squares. */

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("Negative chocolate? YOU MONSTER!");

}

/* If we have zero or one square, there's exactly one way to eat

* the chocolate.

*/

if (numSquares <= 1) {

return 1;

}

/* Otherwise, we either eat one square, leaving numSquares - 1 more

* to eat, or we eat two squares, leaving numSquares - 2 to eat.

*/

else {

return numWaysToEat(numSquares - 1) +

numWaysToEat(numSquares - 2);

}

}

Modify this function so that it counts the total number of ways of eating the chocolate bar, not just with bites of size one and two.

Solution

In the case where all bites were of size 1 or 2, we fired off two recursive calls. Here, when there’s a variable number of recursive calls, we’ll use a for loop to try all bite sizes and fire off the recursive call inside the loop.

int numWaysToEat(int numSquares) {

/* Can't have a negative number of squares. */

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("Negative chocolate? YOU MONSTER!");

}

/* If we have zero squares, there's exactly one way to eat the

* chocolate bar, which is to do nothing.

*/

if (numSquares == 0) {

return 1;

}

/* Otherwise, we will eat somewhere between 1 and numSquares

* squares in our next bite. If we eat biteSize pieces off of

* the chocolate bar, we'll be left with numSquares - biteSize

* pieces remaining. We need to add up all the ways to do this.

* Since we don't have a fixed number of recursive calls to

* make, we'll use a loop to do this.

*/

else {

int result = 0;

for (int biteSize = 1; biteSize <= numSquares; biteSize++) {

result += numWaysToEat(numSquares - biteSize);

}

return result;

}

}

Fun fact: this will always print out \(2^{numSquares-1}\) as its answer, except for when numSquares is zero and it prints . If you’re curious why that is, take Stanford CS103!

Last time, we wrote the following function to print out all the ways to eat a chocolate bar using bites of size 1 and 2:

/* Print all ways to eat numSquares more squares, given that we've

* already taken the bites given in soFar.

*/

void printWaysToEatRec(int numSquares, const Vector<int>& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If there are no squares left, the only option is to use

* the bites we've taken already in soFar.

*/

if (numSquares == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

}

/* Base Case: If there is one square lfet, the only option is to eat

* that square.

*/

else if (numSquares == 1) {

cout << soFar + 1 << endl;

}

/* Otherwise, we take take bites of size one or of size two. */

else {

printWaysToEatRec(numSquares - 1, soFar + 1);

printWaysToEatRec(numSquares - 2, soFar + 2);

}

}

void printWaysToEat(int numSquares) {

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("You owe me some chocolate!");

}

/* We begin without having made any bites. */

printWaysToEatRec(numSquares, {});

}

Modify this code so that it prints all the ways to eat a chocolate bar with no restrictions on the number of squares per bite.

Solution

As above, the major change is a switch from two explicit recursive calls to using a for loop to list off the calls we need to make.

/* Print all ways to eat numSquares more squares, given that we've

* already taken the bites given in soFar.

*/

void printWaysToEatRec(int numSquares, const Vector<int>& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If there are no squares left, the only option is to use

* the bites we've taken already in soFar.

*/

if (numSquares == 0) {

cout << soFar << endl;

}

/* Otherwise, try all bite sizes. */

else {

for (int biteSize = 1; biteSize <= numSquares; biteSize++) {

printWaysToEatRec(numSquares - biteSize, soFar + biteSize);

}

}

}

void printWaysToEat(int numSquares) {

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("You owe me some chocolate!");

}

/* We begin without having made any bites. */

printWaysToEatRec(numSquares, {});

}

Last time, we wrote this function that returns the a Set of all ways of eating the chocolate bar with bite sizes 1 or 2.

/* Returns all ways to eat numSquares more squares, given that we've

* already taken the bites given in soFar.

*/

Set<Vector<int>> waysToEatRec(int numSquares, const Vector<int>& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If there are no squares left, the only option is to use

* the bites we've taken already in soFar.

*/

if (numSquares == 0) {

/* There is one option here, namely, the set of bites we came up

* with in soFar. So if we return all the ways to eat the

* chocolate bar given that we've committed to what's in soFar,

* we should return a set with just one item, and that one item

* should be soFar.

*/

return { soFar };

}

/* Base Case: If there is one square lfet, the only option is to eat

* that square.

*/

else if (numSquares == 1) {

/* Take what we have, and extend it by eating one more bite. */

return { soFar + 1 };

}

/* Otherwise, we take take bites of size one or of size two. */

else {

/* Each individual recursive call returns a set containing the

* possibilities that arise from exploring that choice. We want

* to combine these together.

*/

return waysToEatRec(numSquares - 1, soFar + 1) +

waysToEatRec(numSquares - 2, soFar + 2);

}

}

Set<Vector<int>> waysToEat(int numSquares) {

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("You owe me some chocolate!");

}

/* We begin without having made any bites. */

return waysToEatRec(numSquares, {});

}

Modify this function to allow bites of any sizes, not just 1 and 2.

Solution

This will feel like a mix between the first two approaches. In the first approach, we had to declare a local variable to track the sum from across all the recursive calls. In the second approach, we passed extra information down at each step to track what choices we’ve made so far. Particle acceleratoring them together gives this solution:

/* Returns all ways to eat numSquares more squares, given that we've

* already taken the bites given in soFar.

*/

Set<Vector<int>> waysToEatRec(int numSquares, const Vector<int>& soFar) {

/* Base Case: If there are no squares left, the only option is to use

* the bites we've taken already in soFar.

*/

if (numSquares == 0) {

/* There is one option here, namely, the set of bites we came up

* with in soFar. So if we return all the ways to eat the

* chocolate bar given that we've committed to what's in soFar,

* we should return a set with just one item, and that one item

* should be soFar.

*/

return { soFar };

}

/* Otherwise, we have to take a bite. Try all sizes. */

else {

Set<Vector<int>> result;

for (int biteSize = 1; biteSize <= numSquares; biteSize++) {

result += waysToEatRec(numSquares - biteSize, soFar + biteSize);

}

return result;

}

}

Set<Vector<int>> waysToEat(int numSquares) {

if (numSquares < 0) {

error("You owe me some chocolate!");

}

/* We begin without having made any bites. */

return waysToEatRec(numSquares, {});

}

Tricky Recursion Tracing¶

Topics: Recursion call and return, Tracing

Below is a recursive functions along with an initial call to that functions. Determine what value is returned from the function. As a note, the function contains a bug (or at least, highly misleading code) that makes it not behave in the way you might initially expect. In addition to tracing the function, make a note of what specifically that function does that’s Cruel and Unusual.

int batken(const Vector<int>& v) {

if (v.isEmpty()) {

return -1;

}

int total = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < v.size(); i++) {

total += v[i];

return batken(v.subList(i));

}

return total;

}

// Determine what this outputs!

cout << batken({1, 2, 3, 4}) << endl;

Solution

An important detail to notice in this function is that there’s something broken with how the for loop works: the for loop can never execute more than once. That’s because the last line of the for loop is a return statement, and a return statement ends the current function call. As a result, here’s what happens:

batken({1, 2, 3, 4})returns the value ofbatken({2, 3, 4})batken({2, 3, 4})returns the value ofbatken({3, 4})batken({3, 4})returns the value ofbatken({4})batken({4})skips the for loop because the initial value ofiis equal to the size of the vector, so then it proceeds to return 0.

Therefore, the return value is zero. This leads to this piece of advice:

It is exceedingly rare in any context, and in particular in the context of recursion, to have a for loop that ends with an unconditional return statement.

Optimization and Enumeration¶

Splitting The Bill¶

Topic: Recursion, Combinations, Sets

You’ve gone out for coffees with a bunch of your friends and the waiter has just brought back the bill. How should you pay for it? One option would be to draw straws and have the loser pay for the whole thing. Another option would be to have everyone pay evenly. A third option would be to have everyone pay for just what they ordered. And then there are a ton of other options that we haven’t even listed here!

Your task is to write a function

void listPossiblePayments(int total, const Set<string>& people);

that takes as input a total amount of money to pay (in dollars) and a set of all the people who ordered something, then lists off every possible way you could split the bill, assuming everyone pays a whole number of dollars. For example, if the bill was $4 and there were three people at the lunch (call them A, B, and C), your function might list off these options:

A: $4, B: $0, C: $0

A: $3, B: $1, C: $0

A: $3, B: $0, C: $1

A: $2, B: $2, C: $0

A: $2, B: $1, C: $1

A: $2, B: $0, C: $1

…

A: $0, B: $1, C: $3

A: $0, B: $0, C: $4

Some notes on this problem:

The total amount owed will always be nonnegative. If the total owed is negative, you should use the

error()function to report an error.There is always at least one person in the set of people. If not, you should report an error.

You can list off the possible payment options in any order that you’d like. Just don’t list the same option twice.

The output you produce should indicate which person pays which amount, but aside from that it doesn’t have to exactly match the format listed above. Anything that correctly reports the payment amounts will get the job done.

Solution

The insight that we used in our solution is that the first person has to pay some amount of money. We can’t say for certain how much it will be, but we know that it’s going to have some amount of money that’s between zero and the full total. We can then try out every possible way of having them pay that amount of money, which always leaves the remaining people to split up the part of the bill that the first person hasn’t paid.

/**

* Lists off all ways that the set of people can pay a certain total, assuming

* that some number of people have already committed to a given set of payments.

*

* @param total The total amount to pay.

* @param people Who needs to pay.

* @param payments The payments that have been set up so far.

*/

void listPossiblePaymentsRec(int total, const Set<string>& people,

const Map<string, int>& payments) {

/* Base case: if there's one person left, they have to pay the whole bill. */

if (people.size() == 1) {

Map<string, int> finalPayments = payments;

finalPayments[people.first()] = total;

cout << finalPayments << endl;

}

/* Recursive case: The first person has to pay some amount between 0 and the

* total amount. Try all of those possibilities.

*/

else {

for (int payment = 0; payment <= total; payment++) {

/* Create a new assignment of people to payments in which this first

* person pays this amount.

*/

Map<string, int> updatedPayments = payments;

updatedPayments[people.first()] = payment;

listPossiblePaymentsRec(total - payment, people - people.first(),

updatedPayments);

}

}

}

void listPossiblePayments(int total, const Set<string>& people) {

/* Edge cases: we can't pay a negative total, and there must be at least one

* person.

*/

if (total < 0) error("Guess you're an employee?");

if (people.isEmpty()) error("Dine and dash?");

listPossiblePaymentsRec(total, people, {});

}

Avoiding Sampling Bias¶

One of the risks that comes up when conducting field surveys is sampling bias, that you accidentally survey a bunch of people with similar backgrounds, tastes, and life experiences and therefore end up with a highly skewed view of what people think, like, and feel. There are a number of ways to try to control for this. One option that’s viable given online social networks is to find a group of people of which no two are Facebook friends, then administer the survey to them. Since two people who are a part of some similar organization or group are likely to be Facebook friends, this way of sampling people ensures that you geta fairly wide distribution.

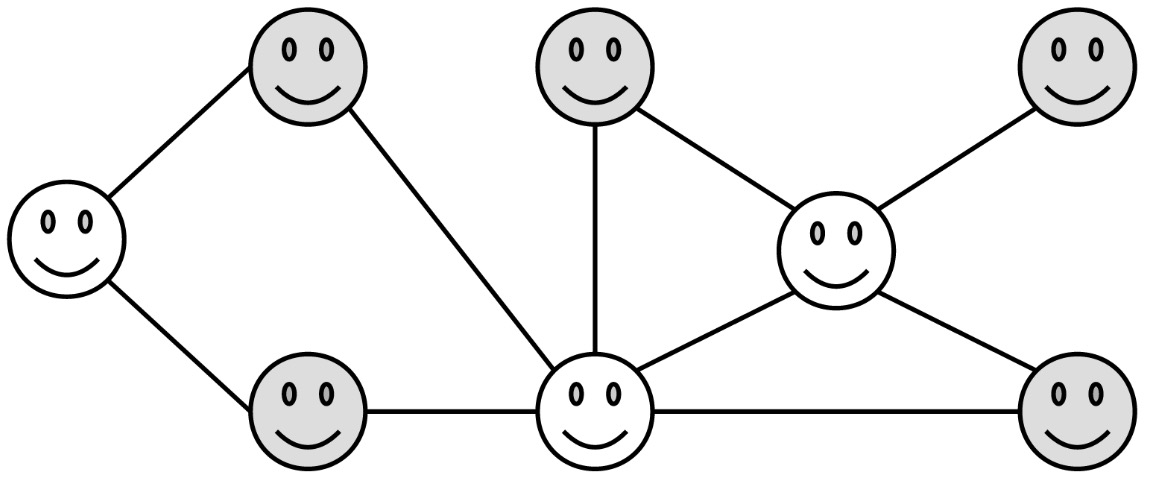

For example, in the social network shown below (with lines representing friendships), the folks shaded in gray would be an unbiased group, as no two of them are friends of one another.

Your task is to write a function

Set<string> largestUnbiasedGroupIn(const Map<string, Set<string>>& network);

that takes as input a Map representing Facebook friendships (described later) and returns the largest group of people you can survey, subject to the restriction that you can’t survey any two people who are friends.

The network parameter represents the social network. Each key is a person, and each person’s associ-ated value is the set of all the people they’re Facebook friends with. You can assume that friendship issymmetric, so if person A is a friend of person B, then person B is a friend of person A. Similarly, you can assume that no one is friends with themselves.

Something to keep in mind: Your solution must not work by simply generating all possible groups of people and then checking at the end which ones are valid (i.e. whether no two people in the group are Facebook friends). This approach is far too slow to be practical.

Solution

One way to solve this problem is to focus on a single person. If we choose this person, we’d want to pick, from the people who aren’t friends with that person, the greatest number of people that we can. If we exclude this person, we’d like to pick from the remaining people the greatest number of people that we can. One of those two options must be optimal, and it’s just a question of seeing which one’s better.

/**

* Given a network and a group of permitted people to pick, returns the largest

* group you can pick subject to the constraint that you only pick people that

* are in the permitted group.

*

* @param network The social network.

* @param permissible Which people you can pick.

* @return The largest unbiased group that can be formed from those people.

*/

Set<string> largestGroupInRec(const Map<string, Set<string>>& network,

const Set<string>& permissible) {

/* Base case: If you aren’t allowed to pick anyone, the biggest group you

* can choose has no people in it.

*/

if (permissible.isEmpty()) return {};

/* Recursive case: Pick a person and consider what happens if we do or do not

* include them.

*/

string next = permissible.first();

/* If we exclude this person, pick the biggest group we can from the set of

* everyone except that person.

*/

auto without = largestGroupInRec(network, permissible - next);

/* If we include this person, pick the biggest group we can from the set of

* people who aren’t them and aren’t one of their friends, then add the

* initial person back in.

*/

auto with = largestGroupInRec(network,

permissible - next - network[next]) + next;

/* Return the better of the two options. This uses the ternary conditional

* operator ?:. The expression expr? x : y means "if expr is true, then

* evaluate to x, and otherwise evaluate to y."

*/

return with.size() > without.size()? with : without;

}

Set<string> largestUnbiasedGroupIn(const Map<string, Set<string>>& network) {

Set<string> everyone;

for (string person: network) {

everyone += person;

}

return largestGroupInRec(network, everyone);

}

Change We Can Believe In¶

Topics: Sets, Recursion, Optimization

In the US, as is the case in most countries, the best way to give change for any total is to use a greedy strategy - find the highest-denomination coin that’s less than the total amount, give one of those coins, and repeat. For example, to pay someone 97¢ in the US in cash, the best strategy would be to:

give a half dollar (50¢ given, 47¢ remain), then

give a quarter (75¢ given, 22¢ remain), then

give a dime (85¢ given, 12¢ remain), then

give a dime (95¢ given, 2¢ remain), then

give a penny (96¢ given, 1¢ remain), then

give another penny (97¢ given, 0¢ remain).

This uses six total coins, and there’s no way to use fewer coins to achieve the same total.

However, it’s possible to come up with coin systems where this greedy strategy doesn’t always use the fewest number of coins. For example, in the tiny country of Recursia, the residents have decided to use the denominations 1¢, 12¢, 14¢, and 63¢, for some strange reason. So suppose you need to give back 24¢ in change. The best way to do this would be to give back two 12¢ coins. However, with the greedy strategy of always picking the highest-denomination coin that’s less than the total, you’d pick a 14¢ coin and ten 1¢ coins for a total of eleven coins. That’s pretty bad!

Your task is to write a function

int fewestCoinsFor(int cents, const Set<int>& coins);

that takes as input a number of cents and a Set<int> indicating the different denominations of coins used in a country, then returns the minimum number of coins required to make change for that total. In the case of US coins, this should always return the same number as the greedy approach, but in general it might return a lot fewer!

And here’s a question to ponder: given a group of coins, how would you determine whether the greedy algorithm is always optimal for those coins?

It’s possible that you won’t be able to make the total. For example, if you’re asked to make 1¢ and only have 2¢ coins, there’s no way to make the total. In that case, return cents + 1 as a sentinel value. This number is bigger than any amount that could actually be needed, and therefore signals to the user that the total can’t be made. On the other hand, if the input is illegal (say, asking for change for a negative number of cents), you should call error to report an error.

Solution

The idea behind this solution is the following: if we need to make change for zero cents, the only (and, therefore, best!) option is to use 0 coins.

Otherwise, we need to pay some amount. To do that, we’ll pick one of our coins - it doesn’t matter which - and ask how many times we’re going to use that coin. That will be some number between 0 and the amount to pay divided by the value of that coin. We’ll recursively explore each of these options, recording which one gives us the best result.

Here’s what that might look like.

int fewestCoinsFor(int cents, const Set<int>& coins) {

/* Can't have a negative number of cents. */

if (cents < 0) {

error("You owe me money, not the other way around!");

}

/* Base case: You need no coins to give change for no cents. */

else if (cents == 0) {

return 0;

}

/* Base case: No coins exist. Then it's not possible to make the

* amount. In that case, give back a really large value as a

* sentinel.

*/

else if (coins.isEmpty()) {

return cents + 1;

}

/* Recursive case: Pick a coin, then try using each distinct number of

* copies of it that we can.

*/

else {

/* The best we've found so far. We initialize this to a large value so

* that it's replaced on the first iteration of the loop. Do you see

* why cents + 1 is a good choice?

*/

int bestSoFar = cents + 1;

/* Pick a coin. */

int coin = coins.first();

/* Try all amounts of it. */

for (int copies = 0; copies * coin <= cents; copies++) {

/* See what happens if we make this choice. Once we use this

* coin, we won't use the same coin again in the future.

*/

int thisChoice = copies + fewestCoinsFor(cents - copies * coin,

coins - coin);

/* Is this better than what we have so far? */

if (thisChoice < bestSoFar) {

bestSoFar = thisChoice;

}

}

/* Return whatever worked best. */

return bestSoFar;

}

}

Social Distancing, C++ Edition¶

There’s a checkout line at a local grocery store. It’s one meter wide, some number of meters long, and subdivided into one-meter-by-one-meter squares. Each of those squares is either empty or has a person standing in it. We can represent the state of the checkout line as a string made of the characters

'P'and'.', where'P'represents a square with a person in it and'.'represents a square with no one in it.Social distancing rules require there to be at least two meters of empty space between each pair of people. So, for example, the string:

has everyone obeying social distancing rules, while the string

does not. Similarly, the string

does not obey social distancing rules.

Your task is to write a function

that takes as input the length of the line (in meters) and the number of people in the line, then returns all arrangements of the checkout line that maintain the social distancing requirements. For example, calling

safeArrangementsOf(12, 4)would return these strings:On the other hand, calling

safeArrangementsOf(8, 4)would return an empty set, since there’s no way to fit four people into a line eight meters long while ensuring everyone is at least two meters apart. (Do you see why?)Solution

There are many ways to solve this problem. These first two solutions are based on the following insight. We’re going to build the line from the left to the right, and the recursive calls will progressively reduce the remaining size of the line until all squares in the line have been filled in. At each point, we have two choices:

We can build another blank square. (You could optionally restrict this to say “we can build another blank square provided that we have enough space to fit everyone else,” which will speed things up a bit but isn’t strictly necessary given the problem statement.)

We can place a person - provided that there are people left to place and provided that this doesn’t conflict with the previously-placed person.

At the end, we’ll have our line of people. Provided that we placed everyone, we can use that way of filling in the line as one of our generated strings. But if we reach the end of the line and haven’t placed everyone - or if there’s no possible way to fit everyone in - we can stop looking and say that no solution exists down this branch.

Here are two ways of implementing this solution. This first one uses the

endsWithfunction, as suggested in the problem statement:This second solution instead includes an extra parameter indicating how far back you have to look to find the most recent person. Aside from that, the core recursive structure is the same.

Here’s a solution based on a different insight. Like the above solutions, this one works by either placing down a blank spot or placing down a person. However, when placing down a person, we consider two options:

That person is the last person in the list. In that case, they can go anywhere in the remainder of the list, and so we’ll consider all ways of placing them down that way.

That person is not the last person in the list. In that case, we place down the person, plus two blank spaces, to ensure adequate separation between them and the next person.

This approach needs to make sure not to exceed the maximum space allowed in the line. There are many ways to do this, and our approach works by ensuring that there’s adequate space to place everyone, stopping as soon as we’re out of room.

Here’s the last of the major solution routes we know of. This approach works based on the following insight. If we need to place a person down, there needs to be some number of blank spots before we see that person. We loop over all possible choices for how many blank spots we put down before we put down that person and try each option to see what we find. This basically takes what some of the above approaches are doing and shuffles around how the recursive calls work. Instead of branching with “place a person” or “don’t,” we only consider the “place a person” option, then decide how many “or don’ts” we’re going to do all at once. This strategy can be combined with several of the above ideas to produce different variants; here’s the one we think is easiest, which works by including an extra parameter indicating how much space we need to leave between us and the previous person (which is zero for the first person and two for everyone else.)